The Admissibility of Blockchain as Digital Evidence

Blockchain is emerging as a disruptive technology with surprisingly diverse applications across a broad range of industries. Organizations are using it to create highly secure, decentralized databases for everything from digital transactions and record keeping to supply chain management and cybersecurity.

Organizations must proceed with caution, however. In addition to the practical and operational challenges that come with the adoption of any nascent technology, blockchain poses a number of legal issues, particularly questions of admissibility as electronic evidence.

The Commercial Importance of Blockchain Technology

Originally developed as a means for creating secure digital ledgers for cryptocurrency, blockchain has quickly proven to be a versatile technology. For example:

Walmart is using it to track produce through the supply chain in an effort to improve food safety.

Health care organizations are using it to ensure the integrity of medical records.

Commercial real estate firms are using blockchain-based “smart contracts” for a variety of transactions.

Oil and gas companies use it for managing global energy trading transactions.

In fact, there are practical uses for almost any industry you can think of. In Deloitte’s 2018 global survey of 1,000 “blockchain-savvy” executives, 95% reported they are investing in blockchain technology and 69% said they expect digital ledgers to replace conventional financial ledgers, inventory tracking systems, and other systems of record.

Given the widespread and expanding uses of blockchain technology, how it is treated in litigation and other business disputes is increasing in importance as well.

How Blockchain Works

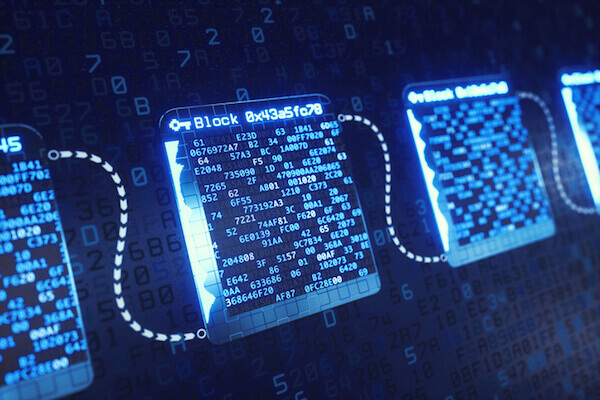

Authors and legal scholars Primavera De Filippi and Aaron Wright describe blockchain as a “distributed, shared, encrypted database that serves as an irreversible and incorruptible repository of information.”

The key phrase here is “irreversible and incorruptible.” Once a block of data is added to a ledger, it cannot be edited or changed in any way. It can only be complemented with new blocks, which are time-stamped and added sequentially. This ensures data integrity by allowing a transparent view of the entire ledger history.

Additionally, blockchain is a decentralized system. Unlike traditional databases, blockchains run on peer-to-peer networks comprising thousands of nodes (computers or servers) scattered across the globe. Copies of the ledger are distributed to each node on the network and updated in real time through a synchronizing algorithm. Having data copied to each node dramatically reduces the risk of data loss or corruption.

If a glitch were to occur, or if someone tried to falsify a record in the ledger, it would be corrected automatically through a “consensus algorithm.” The consensus algorithm operates on the principle that the most widely distributed version of the ledger is correct. The only way to alter the ledger would be to control a large majority of the copies in the network.

The Hearsay Challenge

Despite the virtually incorruptible nature of the technology, blockchain receipts might be challenged in court as inadmissible hearsay. Commonly defined as an “out-of-court statement offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted,” hearsay generally is barred, because the jury cannot assess the credibility of a witness who testifies under oath and the opposing party has no opportunity to cross-examine that witness.

Courts have grappled with hearsay challenges to computer-generated data. In United States v. Lizarraga-Tirado, the question before the court was whether the defendant was still in Mexico or had crossed over into the U.S. at the time of his arrest. Border patrol agents testified that they had recorded the defendant’s coordinates on a GPS device, and prosecutors used a Google Earth image with a computer-generated “thumbtack” to show that the location was within the U.S.

The hearsay objection to the Google Earth screenshot was easily overruled because an image doesn’t make an “assertion.” The “thumbtack” was more difficult because it was generated automatically by Google’s computers. However, the court ultimately ruled that the placement of the thumbtack was not hearsay, because the assertion was made by a machine and not a person.

Codifying Admissibility

Because entries in a blockchain ledger are the direct result of human action, legal scholars have argued that blockchain receipts might fail the Lizarraga-Tirado test. However, blockchain receipt might still be admissible under the “business records” exception to the hearsay rule.

Under Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) 803(6), a record is admissible if, among other things, it “was kept in the course of a regularly conducted activity of a business, organization, occupation, or calling” and “making the record was a regular practice of that activity.” Blockchain ledgers used for business transactions would likely meet these requirements—assuming a sufficient foundation is laid through the testimony or written declaration of a custodian of records or other witness who can lay the necessary foundational facts regarding the circumstances of the documents' creation.

To remove all doubt, several states have taken steps to settle these legal challenges.

In 2016, Vermont passed legislation declaring that blockchain receipts accompanied by a written declaration of a person attesting to the details of the transaction are admissible. Under 12 V.S.A. §1913, blockchain receipts are also presumed to be authentic pursuant to Vermont Rules of Evidence.

Arizona HB 2417 amended the Arizona Electronic Transaction Act to include blockchain records, signatures and smart contracts, which “may not be denied legal effect, validity or enforceability.”

Ohio passed similar legislation in 2018.

And in 2017, Delaware General Corporation Law (DGCL) §224 was amended to allow organizations to maintain business records using “distributed electronic networks or databases.”

In most states, however, legal practitioners must be prepared to address hearsay challenges and ensure that blockchain receipts can be authenticated.

Organizations should also consider these issues when implementing blockchain systems, and be prepared to explain to a court the process of maintaining blockchain records and why they are exceptionally reliable.

Learn More About Law and Technology

To learn more about blockchain and the law, read:

“Blockchain and Beyond: Smart Contracts,” by the American Bar Association

“10 Ways Blockchain Technology Will Change the Legal Industry,” by The National Law Review

“Blockchain and IP Law: A Match made in Crypto Heaven?” by World Intellectual Property Organization

Who’s Regulating Bitcoin and Other Cryptocurrencies? No One.

If you're interested in gaining a better understanding of the issues related to law and technology, such as cyberlaw, intellectual property, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) technology, and virtual law practice, explore Purdue Global Law School’s online Executive Juris Doctor degree and our law and technology courses.