Supreme Court Rules on Racial Quotas in Voting Districts

On March 1, 2017, the United States Supreme Court decided Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Board of Elections,1 a case involving the redrawing of voting districts based on a 55% quota of black voting age population (BVAP). The dispute revolved around whether race was a predominant factor in the legislature’s drawing of the voting districts, and if it was, whether the legislature's drawing of the districts was narrowly tailored to meeting a compelling state interest, thus meeting the strict scrutiny standard. The strict scrutiny standard applies as the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment prohibits the state from establishing voting districts by race without proper justification.

Equal Protection Under the 14th Amendment and the Voting Rights Act

In resolving the dispute, the high court considered the interaction of the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution2 and section five of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA).3 The 14th Amendment states, in relevant part, that “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Section five of the VRA is intended to make sure that in covered jurisdictions, including Virginia, changes to the voting structure are not made unless they can be shown to not “deny or abridge the right to vote on account of race, color, or membership in a language minority group.”4 The challenge for the legislatures and the courts is to apply the VRA to help avoid the suppression of minority voting rights without violating the Act itself or the 14th Amendment.

District Court Finds Race Not Predominant Factor in Eleven of Twelve Districts

In Bethune-Hill, the Virginia legislature needed to redraw districts based on the 2010 census. Voters challenged the redistricting in twelve districts, which was based on a formula with a goal of 55% BVAP. The challenge went before a three-member panel of a U.S. District Court, which determined that race was not the predominant factor motivating the legislature in eleven of the twelve districts. As to the twelfth district, the court found that race was, in fact, the predominant motivation, but that the 55% formula was narrowly tailored to the compelling state interest of not violating the VRA by avoiding the diminishing of black voters’ ability to elect the candidate of their choice.

What Is the Standard for Determining if Race Was the Predominant Motivating Factor in the Redistricting?

The threshold question for the Supreme Court in reviewing the district court’s decision5 was whether race was the predominating factor in the redistricting, for if it was, strict scrutiny applies, and the state must show they are using a narrowly tailored approach to address a compelling state interest.6 The Court found the district court erred in its standard for finding race as the predominating factor. The district court required an “actual conflict between traditional redistricting criteria and race”7 before race would predominate. However, the Court clarified that actual conflict is not required, and the inquiry is not solely limited to portions of the voting district lines where conflicts exist. The problem with solely relying on actual conflict with traditional redistricting methods, according to the Court, is that a legislature could disguise their actions with traditional methods, despite the fact race was a predominating motivation for their decision.

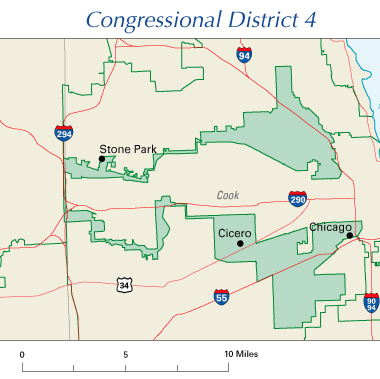

The Court cited Miller to point out that the shape of the district was not dispositive: “Shape is relevant not because bizarreness is a necessary element of the constitutional wrong or a threshold requirement of proof, but because it may be persuasive circumstantial evidence that race for its own sake, and not other districting principles, was the legislature's dominant and controlling rationale…”8 Bizarrely shaped districts are formed through a process known as gerrymandering,9 which is a drawing of voting districts by a political party to gain advantage. Here is an example of a “bizarrely shaped” district from Illinois.10

Therefore, the Court sent the question of racial predominance as to eleven of the twelve districts back to the lower court.

Is Creating Majority Minority Voting Districts Per Se Racial Predominance?

Justice Thomas, in his dissent, disagreed with the majority and argued that intentionally creating a voting district where a racial minority is the majority should automatically be considered predominantly racially motivated. Following that line of reasoning, he argued that strict scrutiny should apply. Justice Alito, in his concurrence, agreed.

What About Judicial Economy?

Justice Thomas took the point of view that the Court already had enough information to determine that race was a predominant factor. Therefore there was no need to ask the district court to rule on that issue. Further, Thomas took issue with the majority assuming, but not finding, that complying with the Voting Rights Act is a compelling state interest. He felt the Court should give clear direction to legislatures and lower courts as to the applicable standards, and should take responsibility for the problems they create when they do not give clear enough direction.

Was the State’s Action Narrowly Tailored as to District 75?

Because the Supreme Court found the motivation for the state’s drawing of the lines in the twelfth district, District 75, was predominantly race-based, strict scrutiny applied. The state needed to show that its redistricting approach was narrowly tailored to a compelling state interest. As noted above, the Supreme Court assumed a compelling state interest. What remained was to find whether the state had good reason to believe the race-based ratio was needed to avoid violating section five of the VRA. The Court found the bipartisan effort and discussions with the incumbent delegate in District 75 were sufficient to constitute a functional analysis and, therefore, that the legislature did undertake a narrowly tailored approach. Justice Thomas dissented, pointing out that no retrogression analysis was done to determine whether the approach was narrowly tailored and suggested the state’s “back-of-the-envelope calculation does not qualify as rigorous analysis."11

The Results and Likely Future of Bethune

The Court sent back eleven of the twelve districts for the district court to review consistent with its reaffirmation of the racial predominance analysis outlined in Miller and Shaw II and the narrow tailoring analysis from Alabama Legislative Black Caucus.12 For the twelfth district, District 75, the Court affirmed the ruling of the district court.

Unfortunately, sending back the remaining districts may well result in more litigation and a “Bethune II” case before the Supreme Court. However, the lower court will at least have the Court’s guidance as to predominance of race as a factor, including not requiring a conflict with traditional redistricting methods and the ability to look at the entire district, rather than the parts in actual conflict, to determine whether predominance exists.

References

1 580 U.S. ___, 2017 WL 774194(2017).

2 U.S. Const., Amend. XIV.

3 52 U.S.C.A. § 10301 (2006)

4 United States Department of Justice, "About Section Five of the Voting Rights Act" (retrieved 3/4/2017).

5 28 U.S.C. § 1253 (2006) allows for a direct appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court in certain circumstances and jurisdiction was granted in this case.

6 Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900, 912 (1995).

7 Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Bd. of Elections, 141 F. Supp. 3d 505, 524 (E.D. Va. 2015), aff'd in part, vacated in part, No. 15-680, 2017 WL 774194 (U.S. Mar. 1, 2017).

8 Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900, 913 (1995).

9 For more information on Gerrymandering, see Christopher Ingraham, "How to steal an election: a visual guide," The Washington Post (May 1, 2015).

10 Illinois' 4th Congressional District, 108th Congress, published in the National Atlas. Retrieved 3/8/2017 from Wikipedia.

11 Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Bd. of Elections, No. 15-680, 2017 WL 774194, at *17 (U.S. Mar. 1, 2017).

12 Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama, 135 S. Ct. 1257, 1259 (2015)